In this interview, architect Emily Jagoda and suprstructur associate Stephanie Manaster discuss past and present projects, jib doors, and gender dynamics in the field of architecture.

Jagoda’s self-designed former residence on Tilden Ave. is currently listed for sale by Nate Cole.

Interview by Stephanie Manaster

Photography by Cody James, Zen Sekizawa, and Monica Nouwens

Drawings by Emily Jagoda

Emily Jagoda, photographed by Monica Nouwens

Do you remember when you realized you wanted to become an architect?

I don't know entirely that there was some “Aha!” moment. But when I was a little kid, I used to measure every piece of furniture in my room and create what I now know is a floor plan. I measured all the windows and the door, and I did a whole little layout on construction paper, and I cut out all the furniture and I would rearrange my twin bed and my dumb little desk. And it was all drawn to scale, but I didn't even know how to use a scale.

I had some friends in college who were taking architecture classes and it just sounded really interesting. I tried it and I liked how challenging it was, and it sort of scratched this creative itch. So it wasn’t a deliberate path - I just kept doing it. Honestly, I'm still not sure I want to be an architect.

I actually decided that I'm going to take a two-year painting sabbatical starting next year. I'm obsessed with painting and I just can't stop thinking about it. And architecture takes so long. I did a house in Palo Alto a few years ago, and I think from the time they hired me till the time we finished the project, it was five years.

A huge thing like that takes so much time to come to fruition, and it makes sense when you think of all the people that are involved and all the things that have to happen, but I really like painting for the immediacy of it.

That sounds like it’ll be a great little change of pace.

Yeah. Even something that takes a long time might only take a few months. I mean, I know of course there are people who will work on a painting for years, but I'm not doing that at this point.

I have to share with you: I actually still do the thing that you did when you were a child, cutting the furniture out of paper and making a floor plan. I’ve moved apartments really frequently over the years and I just started doing it because it's so much easier to visualize everything. I take measurements when I move into a new place, and I just have my little cutouts and flip them around so I know where everything will fit before I move in.

That's great, because you can take a space that doesn't seem like it works, but if you just arrange things in certain ways, it’s like doing a puzzle. Right? Just figuring out how all the pieces fit.

I mean, in a way, this reminds me of the house on Tilden, which I’ve of course been thinking about a lot lately. For that house, there was an existing little bungalow on the front, but I knew before we bought it that we could build a second house on the lot. The new house is basically the footprint of the maximum buildable area. One wall is the side yard setback. The wall parallel to it is the other side yard setback. The distance from the other house is the minimum allowed distance. And then the rear wall is the yard setback - so the footprint is only 650 square feet. You need to pack everything you need in a house into this footprint, so even with three stories, it was still definitely a puzzle. In some ways that building is a three-dimensional diagram of the maximum buildable area of that site.

The exterior of Jagoda's former residence on Tilden Avenue.

It's almost like visual data analysis.

Yeah, exactly. You sift through the building code, and in a way it's really liberating because it provides so many constraints. You’re left with such a sort of short list of things you actually have control over that it's almost freeing. It forces you to find new ways to be creative - for example, I created some really interesting shapes with the roof of the Tilden house. It’s basically two center pitched roofs with different widths and elevations.

In a way, each elevation is just a child's drawing of a house. But then you connect those two facades and you get this crazy shape. The sloped ridge beam is nutty. Then the stairwell is just in a giant dormer, and the bathroom is in another dormer.

There’s this volumetric experience you get when you mix these different roof forms that I found really interesting. When you enter the upstairs space the floor plan is a trapezoid, but the trapezoid meets the triangular slopes of the roof and creates all these weird geometries. It's just a very dynamic space.

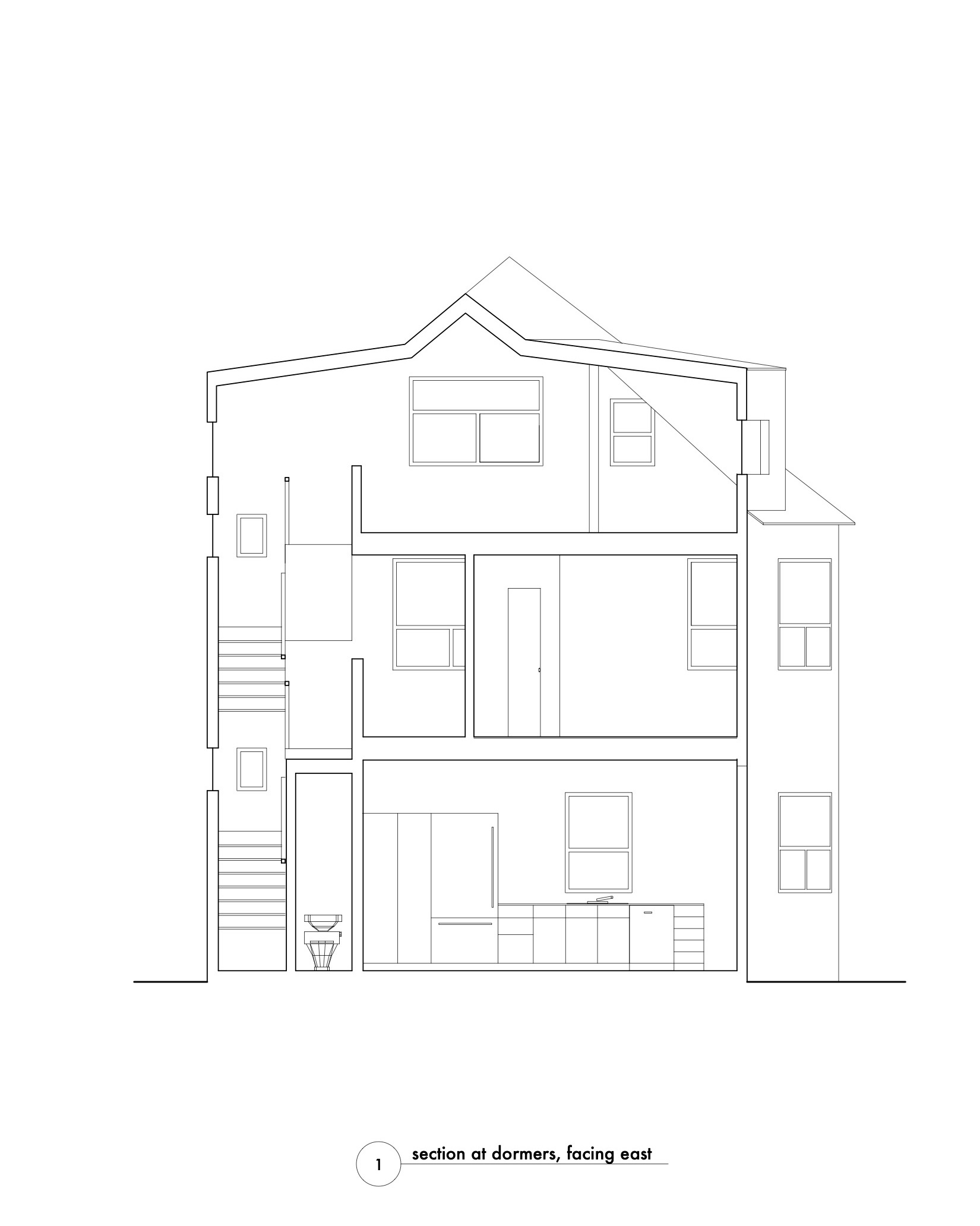

These drawings illustrate the unique shapes and volumes created by the roof of the Tilden house.

Yeah. I have a sense of what you mean after visiting the house. The space feels a little volatile, but in a good way.

This is related to another question I wanted to ask about how you approach a remodel versus a ground up build. Do you feel similarly that the constraints of a remodel force some creativity, or is it a different experience?

There's some overlap there for sure, but it does depend on the remodel. I'm working on one that's an addition to an Eichler. I really like the Eichler style and ethos - I don't always love the fact that they turn their back to the street, but I do really like the way the back of the house opens up onto the yard and engages the outdoors. So, and because the original house has so much greatness to it, it's just so simple - we're really just continuing that slab at grade, having it relate strongly to the exterior spaces, and also building it as a post and beam.

It can be really challenging to build new stuff in that older style because the codes have changed so much. You can't get the spans that they were able to get then, so you have to interrupt the spans with additional structure. In a way it's definitely limiting, but for other remodels that are less architectural I might do a more stylistically different addition, which is a challenge in itself. Sometimes it is about finding the great elements and amplifying them, or riffing on them, sometimes playing around with scale or materials.

Warm wood tones fill the Tilden house and add flair to the miniminalist design.

I did pick up on a few stylistic trademarks looking at your projects - the raw wood, super bright pops of color, and just a million windows and skylights. Can you share a little bit about the influences behind these signature elements?

Such an interesting question to think about. Honestly, most of my projects have unique influences. Gehry and Neutra are references - obviously all the exposed framing is really Gehry, Fred Fisher, the whole Santa Monica school. But I’m also really influenced by Andrew Geller, this Long Island architect in the fifties. He did this house called the Pearlroth House, which is essentially two diamond-shaped volumes next to each other on the beach in West Hampton. I used to look at that house through binoculars from my grandparents’ house across the bay. All of his work has this really raw simplicity to it.

Part of that, again, is the fact that the building codes weren't what they are now. Now you can't just frame studs and put siding on it and call it a day. You have to actually insulate it and finish it out. It's much harder to build with that sort of immediacy of materials. But I really appreciate that look, and I like that it has this sort of impromptu or sketch-like quality to it. It feels much more free. There are a couple more Long Island architects I reflect on a lot - Norman Jaffe, for example - in general I really appreciate that seventies “Long Island Modern” style. I would say that’s my earliest influence, and then it's run through the Gehry filter.

The third floor bedroom at the Tilden house is a lofted space that highlights the home's unique roof shape.

I was going to ask if you consider your style distinctly Californian, but it seems like there’s a good amount of East Coast influence there as well.

Yeah, for sure. I mean, there's so many great architects. Actually, one other Long Island guy is Myron Goldfinger.

Awesome name.

Yeah. Totally. I feel like Geller, Jaffe and Goldfinger are probably my all time favorites. I also really love Ray Kappe and he is a huge influence. He would often take projects on sites that nobody else wanted. His own house has that stream running through it - back then nobody would buy a lot with a stream on it, because that's a nuisance, but he just found a way to make the house specific to that site. The whole idea of making your project site specific is not unique to those folks, nor to me. But it's I think one of the critical elements in elevating something from just a building into capital "A" Architecture.

Jagoda renovated an existing 1930's bungalow on the same lot as the Tilden house.

It’s interesting hearing about these Long Island architects who have influenced you - I see so much reciprocal influence between California modernism, specifically the SCI-Arc school, and these East Coast projects.

Speaking of SCI-Arc, I was curious if there was a lot of contrast between the experience of studying there for grad school versus Columbia for undergrad.

Yeah, for sure. They were very different. Columbia was more formal - the interest in the avant-garde was almost academic. SCI-Arc is the avant-garde. Studying at SCI-Arc also had this sort of hands-on immediacy to it. However, SCI-Arc has changed so much since I was there - some aspects of what the education was like at that time might've been pretty specific to who was teaching there.

But so many of the people who've taught at SCI-Arc were really actively building stuff and weren't necessarily strictly academics. The discourse was a lot more about vernacular architecture - taking ideas from vernacular architecture and then playing with the scale is something I've definitely taken with me.

On the other hand, I love taking traditional architectural concepts, whether they’re vernacular or classical or whatever, and turning them around, flipping them on their head - just playing with it.

For example, in one of my recent projects, I played around a lot with jib doors. When that door is shut, you don't see any hardware or hinges or anything - it's just a touch latch door that pops open to reveal this other space. When it’s all the way closed, it conceals a small office space, and when it’s open, it looks like a bookshelf that’s flush with the other built-ins on the wall.

The jib door at the Mahony May studio, open...

...and closed.

I love these little multipurpose details. That's such a California mid-century thing. A lot of the Case Study Houses have those features, for example.

Right. There's something about the jib door that just... I don’t know, I’m drawn to it.

I think the most well-known jib door is in the oval office. So if you ever watched The West Wing, they're always going in and out through the jib door. It's so great because it's a curved room and the molding goes all the way around, and then there's just this little cut - then this curved door swings open. It's so weird. I'm not sure what's so compelling about that. I think again, maybe it's that act of transforming the space with just one action. And I love that it doesn't announce itself; it's completely concealed. It's like cutting open a watermelon. You have this green thing and then you cut it open and it's red on the inside. I feel like that's the great surprise that you get from the jib door. Right? It's like a watermelon.

The Mahony May studio has a second jib door leading to the bathroom.

Yeah, I love that too. Even if everything else about a space is simple and minimalist and pared down, those little unexpected touches can make you go, “wow!” - there's just an element of fun to it, which is great because architecture can feel so utilitarian sometimes. Anything that makes someone have a little moment of excitement in that space is really special.

For some reason that reminds me of the Fabergé eggs. They're decorative on the outside, but who would guess that you can take this delicate thing and crack it open and reveal this whole little world inside it. The idea that the exterior belies the interior, right?

Many of Jagoda's projects feature splashes of neon color.

Fabergé, Easter, Kinder Surprise eggs. Real eggs, honestly.

That reminds me of a story related to eggs and architecture. I don’t think any of this was officially recorded, but I like to believe it's true.

There was a competition to determine who would design the dome of the Florence cathedral, and the final two architects in the contest were Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi. They had to submit their plans for the dome, and the judges didn’t believe that Brunelleschi’s plan for an innovative double-walled brick structure would actually hold. Brunelleschi challenged all of the judges to a challenge in order to prove his point - the task was to make an egg stand upright. The judges tried and failed until Brunelleschi took his egg and cracked the bottom onto the table, making it stand upright.

The judges said, “We could have done that ourselves!”

Brunelleschi responded, “You could build the cathedral’s dome yourselves, too, if you had my designs.” As the story goes, that’s why he won the contest and received the commission to design the dome. The story about how they chose the architects to build the Duomo in Florence.

That's great. That’s some early outside-the-box thinking.

Yeah. Like I said, even if it’s not true, I hope it is.

Light fills the Tilden house from numerous windows, which also form a passive cooling system throughout the space.

Anyway, thanks for listening to that little tangent. It does kind of strike me that throughout history, from way back in the Renaissance through today, the field of architecture continues to seem like such a boys’ club. Not only architects themselves, but people who are interested in architecture - it’s so male-dominated. I don't know if that aligns with your experience, but I am curious if you have any perspective on this. Do you see it changing anytime soon?

It is such a boys club. For sure. I do struggle with that - I've had to learn certain tricks. In any project, my main strategy is to be hyper competent and super nice, but sometimes you have to make it clear that you're not going to be belittled or diminished by anyone. It can be anything from people working on site referring to me just as “she” - it’s such a weird red flag when someone doesn't want to just use your name or your title. It doesn’t always reflect this attitude, but when you hear it over and over it can mean that they don't want to take you seriously. That you're not an individual, you're an obstacle or something. I always want to see the good in everybody, but you also have to be a little bit on guard for when you're not being taken seriously.

So yeah, it's a huge boys' club. I'm used to showing up at the site and people saying, “Oh, are you the designer?” And then I have to say, “I'm the architect.” Not the Southern California style, “I'm the architect?” like it’s a question - I have to say, “I'm the architect, period.”

It is helpful to find a community of allies. I think it is especially important to be a champion of other women's careers. You also need those people in your circle who you can call and say, “Okay. So when I read this section of the code, I get that I can do 42, but could I do 36?” You also need those people that you can just bounce little dumb questions off of.

I’ve had to develop pretty good radar to avoid working with people who don't take me seriously, or who hire me just because I'm nice. That's actually the kiss of death. If somebody hires you just because you're nice, they may not want to hear your advice. The worst thing of all is when you have to talk someone into making the right choices because they don’t trust your expertise. I don't want to have to pitch it to you; I don't want to have to talk you into doing what's right. You should trust me because I know.

Maybe that's part of why painting appeals to me, too. You just make a thing and then you're like, okay, here's the thing. If you want it, it's yours. If you don't, we're good. But there’s no one telling you to make it a certain way.

The ground floor living area at the Tilden house features plywood accents and high ceilings.

Yeah, that completely makes sense as well. It's already done. The customer doesn't have any input, basically.

That makes me sound like an asshole. Maybe it's a phase.

Isn’t being an asshole a good thing sometimes?

It is. It's hard though. Especially for women because our culture doesn't like us to be outspoken, opinionated, bossy.

Yeah. I can well imagine how exhausting it is to be in your position, when you're dealing with projects involving so much time and money, and so many people, and so many variables. It's a lot of stress on top of a lot of stress.

Yeah. Seeing the Tilden house so much in the last few weeks since it hit the market has made me really miss being the client. It's just so nice to be able to really call all the shots. I mean, it's also very weighty, because there’s no one to help you make these big decisions, but I miss it. I want to do it again. I want to build something else again, because it's also really instructive to build something and then live in it.

I can imagine. Give me a few years to save up and I’ll hire you to build me something, anything you want it to be, and you can live in it for a while before I move in.

Let's go build something off grid and we won't pull permits. Kidding.

Yes, okay. Deal. Off the record.