In the independent documentary Welcome to my Eichler Home, director Robert Wiering investigates Joseph Eichler's legacy as a champion of design-centered affordable housing. Mr. Wiering describes how he was drawn to Eichler's story and inspired by his homes during a trip to the Bay Area.

Interview by Stephanie Manaster

Photography by Joe Fletcher and Ernest Braun

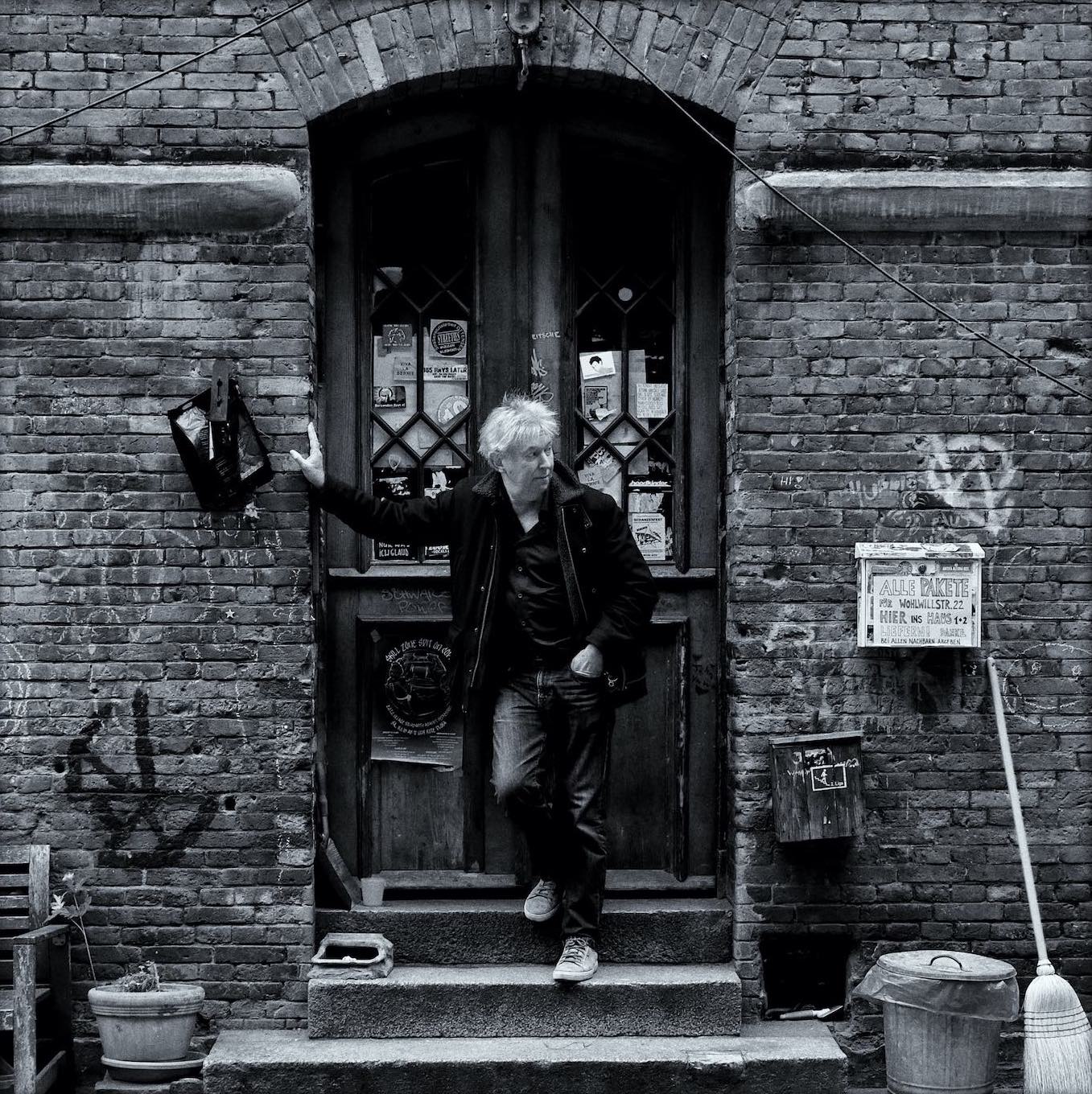

Filmmaker Robert Wiering, photographed by Hansje van Etten

Could you tell us a bit about your background as a filmmaker, as well as your interest in architecture and design?

After high school, I studied psychology for about ten minutes, and then I thought it would be better to go to art school. I have an education in design and also making films. One of the films I made sold to a public broadcasting company in the Netherlands called VPRO, and I've been working for them for more than thirty years as a producer, director, and developer. I cooked up a lot of ideas in the eighties, when there was a lot of creative freedom. I did fiction and nonfiction programs, programs for children and for grownup people, low-budget drama and big-budget drama.

I made a series for VPRO about buildings in Holland called Stealing Your Lands. We offered a platform to people who were concerned about other big buildings coming in their neighborhood, and we stopped a lot of nonsensical building projects. I got to know a little bit more about how developing and building takes place. It was a lot of fun, and I got to know my friend Edwin Oostmeijer, who is a developer of very beautiful building projects. I made a few little movies for his developments.

When 2008 came and everything collapsed, Edwin started organizing trips to San Francisco for Dutch architects to see the mid-century housing there, just out of his own interest. Then, in 2013, the government made very big cuts in the budgets for public broadcasting. I left VPRO and Edwin said, "Come with me to San Francisco just to get some inspiration." So we went to all those Eichler buildings, and all kinds of buildings around the Bay Area, and it was very beautiful.

Many Eichler floorplans feature an open atrium, expanding outdoor living possibilities.

Was this when you became interested in Eichler homes?

Yes, it was. On this trip, I met Catherine Munson, who had been a sales agent for Eichler. We started to think that there is a story to be told about Eichler. I thought that she would be the centerpiece of this documentary, but unfortunately, she died shortly after we met.

I liked her very much, and I had the opportunity to film her with my Fuji X100 camera. I got a little bit of footage where I said to her, "Ms. Munson, can you sell me an Eichler home one more time, like you did so many times before?" And she said, "Sure, honey." I got that on camera and it was wonderful.

So I had that footage and I thought about how many other people were involved in Eichler’s neighborhoods. We got a little funding in the Netherlands so my wife and I could do an independent film. She did the microphone, I did the camera - we did it all with existing light and on a very small scale. We went to San Francisco and filmed for ten days, which is extraordinary, that’s very many days. In public broadcasting, you cannot do that, but as an independent filmmaker, your only cost is your own time.

Glass walls lead to the backyard in many Eichler homes, inviting views of nature into the living space.

I’m surprised that you only filmed for ten days - I know you said that it was a long time, but I think you got so much in a little more than a week.

In public broadcasting in the Netherlands, people have to do an hour-long documentary in two days, flying all the way to Africa or I don't know what. I've been very fortunate to have enjoyed the time when there were bigger budgets. I once made scientific programs regarding human nature, and I could fly all the way to America to portray a psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. It was very chic, but that was in 2006 or so. Ever since, the budgets keep getting smaller. So I’ve done a lot of crazy stuff too, funny stuff, bizarre stuff. Being an art student by education I'm used to improvising. I can do it with great budgets, and I can do it with no budgets. So right now I'm still an independent filmmaker, and by keeping it all small, not having large crews, et cetera, you can make interesting movies.

That’s how I had the opportunity to portray all these people and make this film. After we shot the movie I connected with another public broadcaster in the Netherlands. I said I want to show this movie, and they said, "Oh, no, no, no, we don't have any money." I said, "I don't want your money, I just want your time." So I cut a shorter version of the movie that has been broadcast in the Netherlands, then I also made the longer version, which is on Vimeo. That's how Welcome to my Eichler Home came to be.

An early advertising photo for Eichler homes by renowned photographer Ernest Braun.

Eichler gave people a vision of happiness.

Were you interested in architecture for a long time before making this film?

Ever since I was a kid, I was intrigued by the shape of things - the design of cars, of the Jaguar E-type, things with beautiful design. A few years ago I did a documentary about tiny houses. In the Netherlands, everybody heard about tiny houses and it seemed a bit like hippy stuff, but it turned out there were very great architects who made fabulous tiny houses. In the documentary, I filmed these very high quality houses that were being made and placed in the center of the city of Almere, near Amsterdam. I filmed a tiny house that came all the way from Estonia - it came on a truck and got delivered as if it was a brand new MacBook Pro, but it’s actually a little house. Right now I'm being asked to cover another developing project in Almere. So architecture and buildings have become a part of my heart, so to speak.

Do you see connections between the architecture of Eichler homes and architecture and design trends that you see in the Netherlands?

You cannot really compare it because of the California weather. Eichler homes are all post and beam construction; they're very elegantly made with very big windows and an indoor atrium. The atrium would not be possible in the Netherlands because of our climate. But you see, all the architects that my friend Edwin Oostmeijer took to San Francisco and the Bay Area were all very much influenced [by California design]. So we see a lot of buildings right now in the Netherlands that have those great windows, and very tall ceilings so there’s more light.

I wanted to portray the man, the stubborn man who went against all the rules...everybody who had worked with him loved him and spoke so highly of him.

Eichler himself was not an architect, but a real estate developer. He employed talented architects to create open, light-filled homes that were cutting edge in the mid-century affordable housing market.

What did you most want to portray about Eichler and his homes in this film?

The film is not only the story of Eichler as a person, as a very stubborn person, but also why his developments came to be. After the Second World War, all those veterans needed housing and [the G.I. Bill] said if you could lay 300 bucks on the table, the government would finance the house. There were also the new highways, freeways, and cars so you could live outside of the big city. This is where Eichler saw his chance, but he was exceptional for wanting great architecture and great design in his housing developments.

What I saw was in the great tradition of architect Richard Neutra. Neutra believed that the outside and the inside of a home should be connected. If you have a lot of beauty outside of your house, then a small house will feel a lot bigger and you'll be happy. And I saw that with my own eyes. It was true in the Eichler buildings. Eichler lived in a Frank Lloyd Wright house for a time, and he was inspired by that house. He wasn't a developer at that time, he was actually in the dairy business, but he thought, "Why can't this beautiful architecture be for normal people?"

Eichler made housing for people to be happy, which really touched me. Good design makes you happy. It was astounding that the Eichler homes really had that; they stood out. Everybody who now has an Eichler home is very proud of it.

It was very rewarding to portray this man and this time in America. I wanted to portray the man, the stubborn man who went against all the rules and who wasn't trained in architecture whatsoever - but he was clever, he was a very good businessman, and everybody who had worked with him loved him and spoke so highly of him. And it really warmed my heart.

The windowless façade of an Eichler home sequesters interior views from the street. This creates privacy and balance with the glass walls that lead to the backyard and atrium.

What was your favorite thing that you learned about Eichler and his homes while producing this documentary?

I was very intrigued by the photographs of Eichler homes by Ernie Braun. They were very wonderful. This was during a time when architecture was being sold by saying how much of a garden you had, or how many rooms. But Eichler gave people a vision of happiness. That's best portrayed in the Braun photographs, in which we also can see Catherine Munson as a model, sitting at a dining table in one of the houses. Braun’s photographs were portraits of friends, not professional photography models.

But the best thing I filmed was Catherine Munson, when she “sold” me an Eichler home one last time. That's why the whole film is in her loving memory.

When Eichler was developing The Summit, his high rise building in San Francisco, Catherine Munson cooked up an idea for advertisements. She took a Volkswagen Beetle and she towed it vertically up the side of The Summit with a sign saying, "Eichler buildings: for people on their way up."

Eichler's salespeople would often model for promotional photography. Catherine Munson is seen sitting at the dining table in this Ernest Braun photograph.

You can watch Welcome to my Eichler Home from Robert Wiering on Vimeo.