Lost just a few years after its completion, Albert Frey’s original Palm Springs home was a playful, experimental masterwork of architecture

Photography by Julius Shulman

Story by Jack Byron

Approaching Palm Springs from the direction of Los Angeles one travels the serpentine Route 111 over high desert plains and elegant 1930s bridges to arrive at an oasis of manicured green lawns and swaying palm trees. The first building to greet the visitor is perhaps also one of the city's most iconic with its soaring hyperbolic paraboloid roof.

The Tramway Gas Station, designed in 1965 as an Enco service station, is now home to the city's visitor center. Like many of Palm Springs' most intriguing edifices the building was designed by Albert Frey, a modest Swiss architect, who was arguably one of the most inventive of the modernist emigres to settle in California.

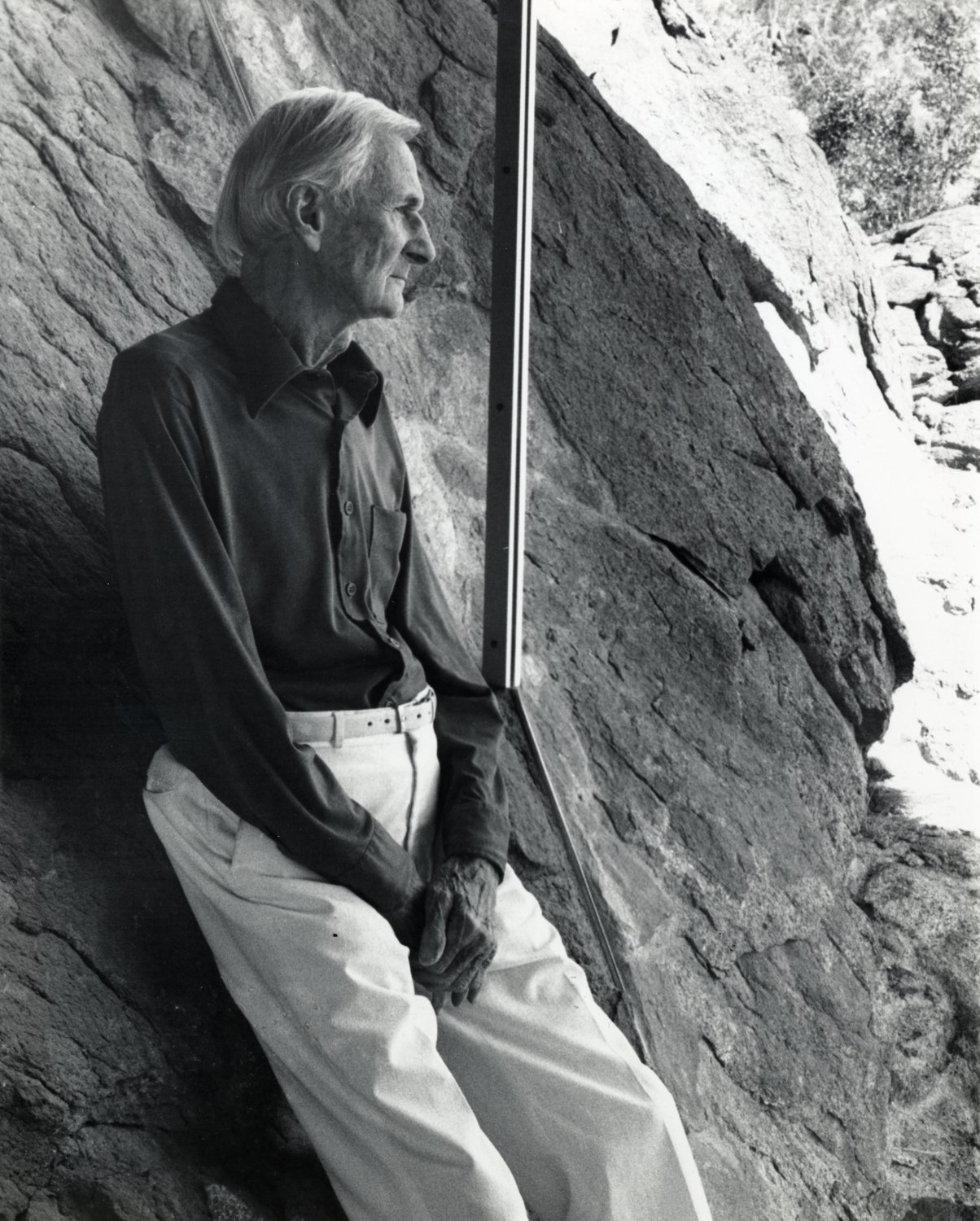

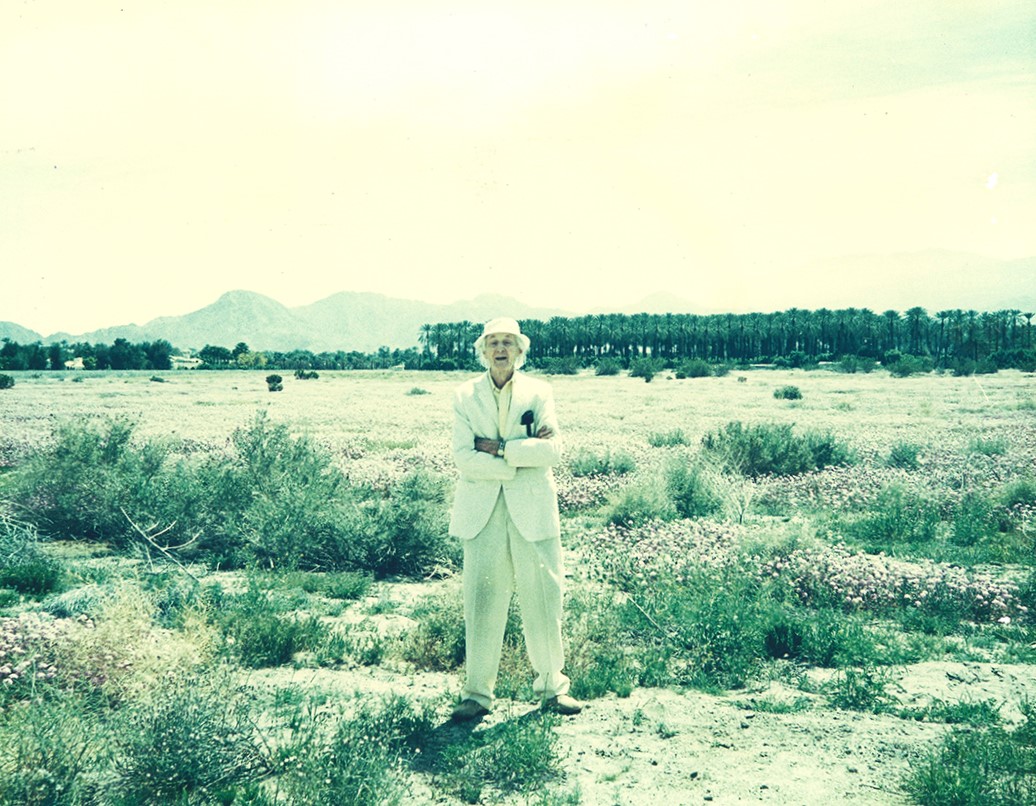

Frey (1903-98) grew up in the foothills of the Alps near Lake Zurich and completed his architectural studies apprenticed at Le Corbusier's atelier in Paris. After graduating, Frey came to Palm Springs in the 1930s by way of New York and was immediately impressed: ‘Palm Springs provides the rare pleasure of combining a magnificent natural environment with being a center for interesting and varied activities. Moreover the sun, the pure air and the simple forms of the desert create the perfect conditions for architecture.’

the sun, the pure air and the simple forms of the desert create the perfect conditions for architecture.

Frey and his building partner John Porter Clark would go on to design the city hall, aerial tramway station and numerous residential and commercial commissions throughout the city, but his most noteworthy works were the two houses he built for himself: Frey House I and Frey House II.

Frey House I

Frey House II

Here we consider the enduring importance of Frey House I. Built between 1940-1953 it now only exists in the photography of Julius Shulman, a friend of Frey's and a regular house guest. Frey House I proved to be a laboratory for experimenting with radical built forms that still have the power to confuse, shock and impress over half a century later.

The building had three distinct lives: 1940 Miesian cube, 1948 avant garde Corbusian villa and finally in 1953, something entirely of Frey's own invention that still defines easy classification.

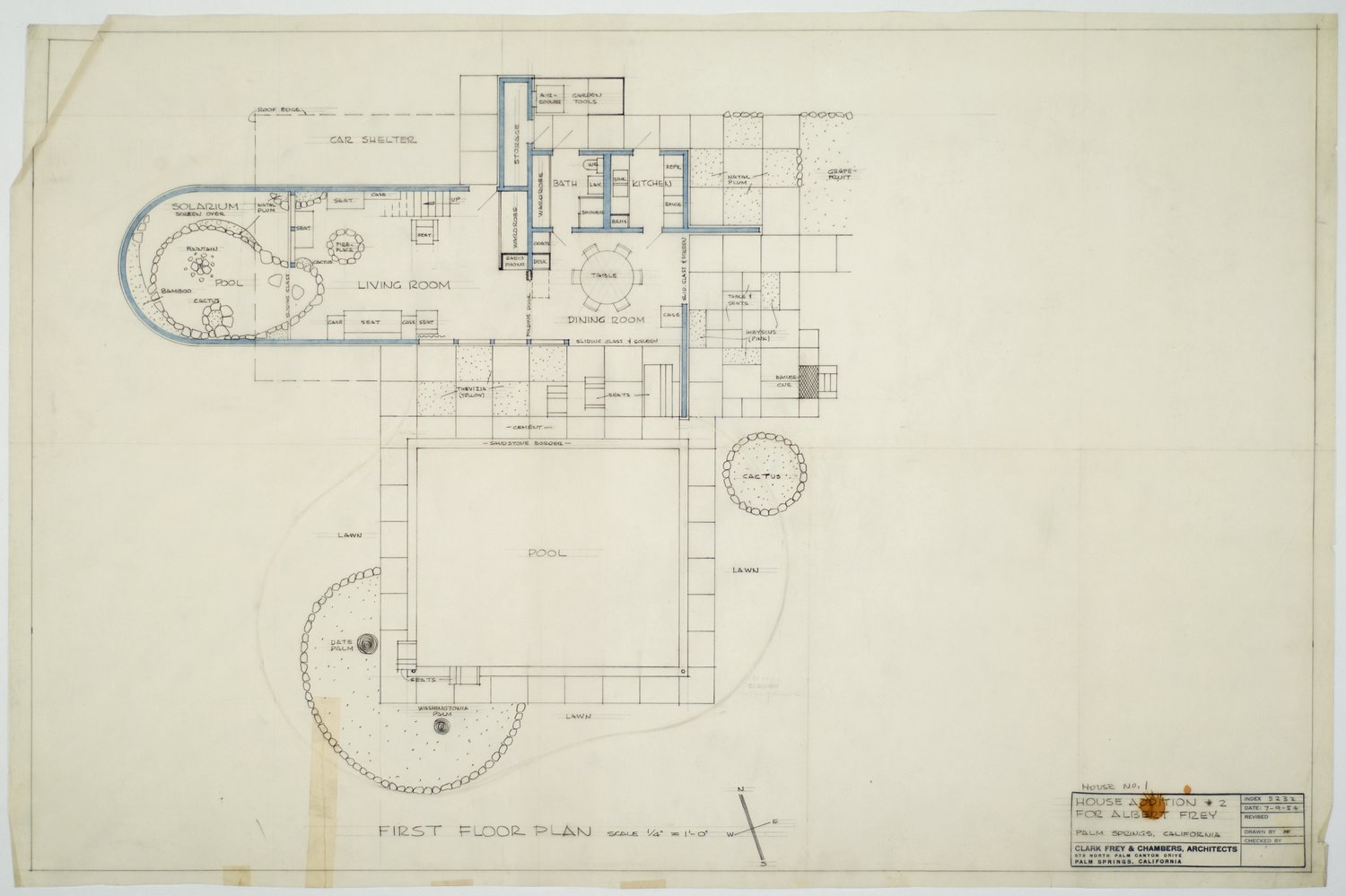

Frey acquired the two acre parcel on Paseo del Miramar in 1940 and set to work constructing a modest pavilion, one of the very first modern structures in the Coachella Valley. A mere 320 square feet, the building encompassed only the bare essentials of shelter: kitchen, bathroom and bedroom. Though diminutively sized, Frey used ‘wing walls’. interior walls that projected into the landscape. In concert with floor-to ceiling glazing this had the effect of extending the building out into the desert floor and thus far beyond its actual confines, an effect Frey modestly attributed to Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona Pavilion.

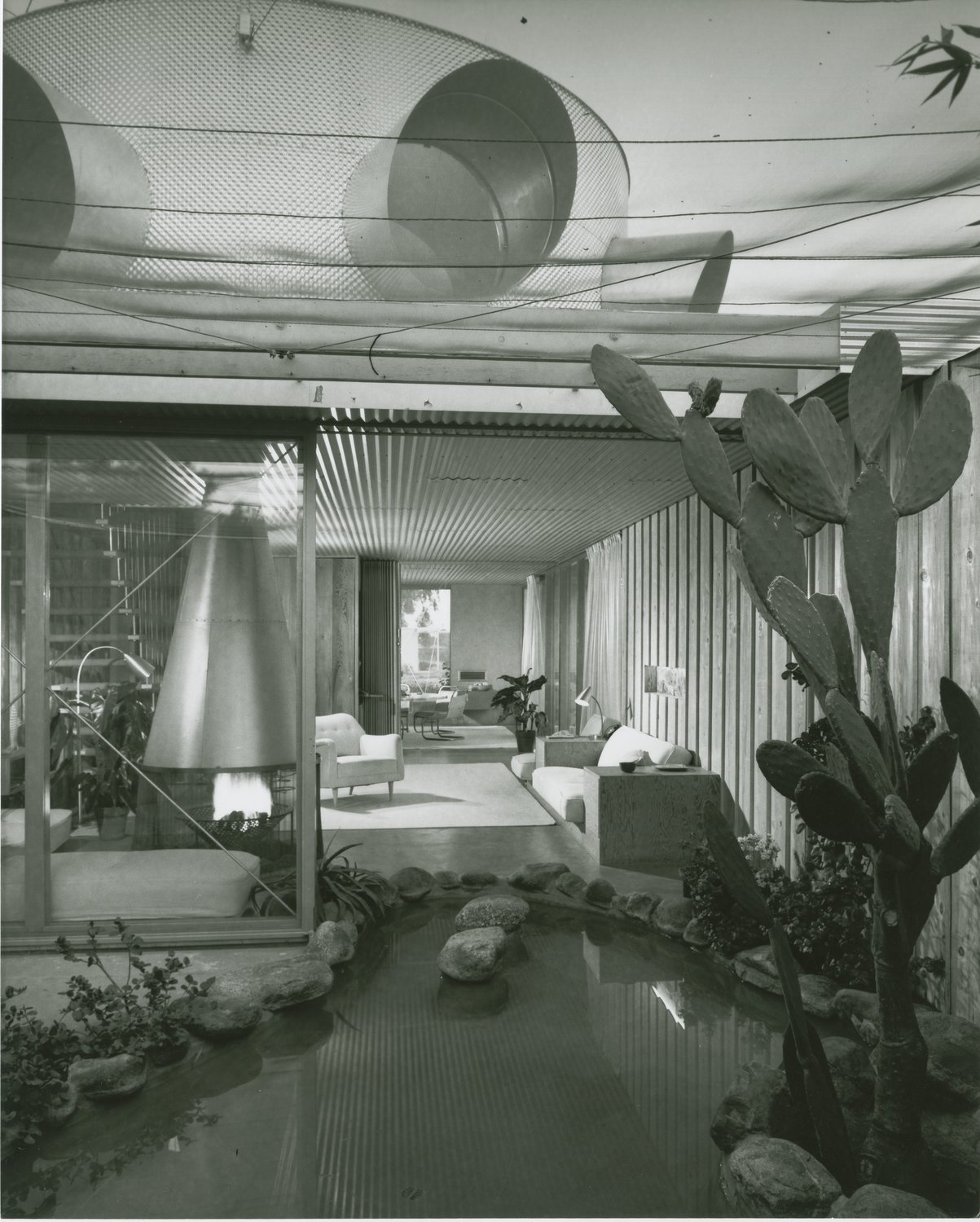

Sliding, full-height glazed doors further expanded the sense of space outwards to a patio and pool which featured a series of in situ concrete seats covered with colorful cushions, as much sculpture as functional architecture.

Externally the building's roof plane had deep overhangs for protection against the sun and desert winds. Sheathed in corrugated aluminum and cement board, the materials were tinted pale pink and green on the interior whilst the corrugated metal ceiling was painted blue. As Frey would later remark: ‘color is so important because it ties in with the surrounding nature. And there should be some contrast with nature. For instance, these technical materials like metal become more dramatic when you look at rock which is natural. It makes a rather exciting contrast’.

color is so important because it ties in with the surrounding nature. And there should be some contrast with nature. For instance, these technical materials like metal become more dramatic when you look at rock which is natural. It makes a rather exciting contrast

The building was marked by a sense of economy, both formal and financial, that was to become a hallmark of Frey's work. "I'm much more interested to get the most from the least amount of money. It’s a challenge that way. It’s easy to splash and spend a lot of money, but that’s not very interesting”

Frey continued to study the desert environment and consider his architectural response to it. In 1948 several changes were made including a living-sleeping area with a skylight for star-gazing, a fanciful indoor-outdoor pool with curved corrugated metal sides and solarium garden complete with wild grape vine, fountain and rustic stepping stones. The solarium and living area were enclosed by a curvilinear wall of translucent rose and yellow colored fiber glass. Frey: ‘that was a structural challenge...you see like a water tank: it’s corrugated and stands up by itself on account of the curve. So it’s only a wall of 16th of an inch thick, you might say, instead of a heavy wall of some sort...I like to do things with the least amount of material’.

Further formal minimalism was explored in a fantastic suspended dining table, later described by Frey: ‘instead of having big bulky legs to support it, these are actually clothes-line-type plastic-covered metal cable that I used. I figured out the weight and triangulation of the table so it wouldn’t move.’

In 1953 Frey transformed the building into what would be its final iteration. A circular second story, accommodating a master bedroom, was added in the form of a round tower with a series of porthole windows tracking the desert panorama and the passage of the sun. Each window was wrapped in a uniquely dimensioned metal visor, the depth of each adjusted to the particular angle of the sun. Frey described his inspiration for the form of the addition: ‘Thomas Jefferson had a second floor which was more octagonal. Then I remembered a Mayan star observatory I had seen in Chichen Itza called The Tower of the Sun, a round building with little windows.’

The tower’s facade was aluminum embossed with a diamond-pattern, whilst internally the walls consisted of tufted yellow fabric with contrasting blue drapes and ceiling tiles.

I remembered a Mayan star observatory I had seen in Chichen Itza called The Tower of the Sun, a round building with little windows.

Perhaps inspired by the earlier hanging dining table, the second story was accessed by a staircase which was pure theater: suspended from the ceiling by a shimmering maze of 1/4” diameter aluminum rods.

The completed building represented something far beyond the rigid confines of contemporary Southern Californian modernism. In many ways it was more a natural progression of Corbusier’s sculptural, almost hand-made, architecture. Frey had achieved a delicate balance with nature, both respecting and contrasting his architecture with the surrounding desert environment and elevating a functional shelter to an experimental, memorable and emotional space.

By the early 1960s Frey had moved on, literally, and was building a second house for himself two hundred feet above the desert floor in the foothills of the San Jacinto mountains.

The original house and its two acre lot were sold to a developer who promptly bulldozed Frey’s hacienda to make way for a subdivision. The hapless developer went bankrupt shortly afterwards and never realized his plans.

The loss of Frey’s building and his unique utopian vision is a tragedy not only for Palm Springs, but also for architecture generally. Rarely is an unfettered artistic vision allowed to flourish quite so vividly as it did, briefly, at 1150 Paseo del Miramar.