Andrew Romano's book "A Walker House - RM Schindler", published for the first time online in its entirety here, tells the charming story of how he ended up living in his dream house in Los Angeles.

Story by Andrew Romano

Photography by Andrew Romano and UCSB archive

Los Angeles is a land of dream houses. It always has been. A century ago families from Omaha and Dubuque came west dreaming of oranges and ranchos and mid-afternoon siestas, and the smart little Spanish Revivals they built, with their evocative arches and roofs of red tile, embodied that reverie. Before long Hollywood devotees began to realise, in residential form, the far-flung visions they were seeing on screen: ‘Samoan huts, Mediterranean villas, Egyptian and Japanese temples, Swiss chalets, Tudor cottages’ of paper and plaster, as novelist Nathanael West once observed—homes that obeyed ‘no law, not even that of gravity’. Today’s developers are no different. They bulldoze the hilltops of Bel-Air, constructing $100 million chateaus on spec; eventually, they wager, some excessive baron will bite, as much for the 14 bathrooms as for the fantasy of endless abundance they convey.

All of which is to say that I shouldn’t be surprised I found my dream house in Los Angeles. But somehow I still am.

In October 2017 my wife and two kids and I moved into a house with a name: the Ralph G Walker House. The reason our house has a name is not because its original owner, Ralph G Walker, had a name worth knowing—he worked for an insurance company—but because his architect did. Walker’s architect was RM Schindler. Schindler arrived in Los Angeles in 1920, 15 years before Walker hired him, and the work he built during that decade and a half (and beyond) was both miraculous and maddening. Miraculous because it was better than nearly all of his contemporaries’, and maddening because it managed to attract far less attention than anything nearly as good.

Schindler was born in Vienna, where he studied under Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos. Before landing in Los Angeles he assisted Frank Lloyd Wright in Wisconsin. It was Wright who sent Schindler to California as a surrogate of sorts, to oversee his projects in the region. The arrangement didn’t stick. By early 1922, Schindler had already broken ground on a house of his own, at the edge of a bean field in West Hollywood, that was more radical than any building yet designed by either Wright or the European masters who would soon claim the mantle of modernism: Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius. With its flat roof, communal plan, large window walls, openness to the outdoors, and primal palette of concrete, canvas, copper, redwood, and glass, Schindler’s home and studio on Kings Road could have qualified as the world’s first fully modern residence—if anyone had known about it. The place wasn’t published until 1932.

Not all of Schindler’s work suffered the same neglect; his houses appeared in the magazines from time to time. But in the end Schindler believed that his ‘architectural problem’ could not be ‘reproduced on paper’. His problem—his medium—was what he called ‘space’. Let other architects trifle with style, he declared in 1912; let them ‘freeze contemporary whims of owner or designer into permanent tiresome features’. He would arrange space itself into ‘a quiet, flexible background for a harmonious life’. In a practical sense, this meant that Schindler’s houses were stubbornly idiosyncratic: intricate puzzles of interlocking volumes tailor-made to respond, in three dimensions, to the particular parcel of land they occupied, the particular view they faced, the particular arc of light that fell upon them, the particular clients they sheltered, the particular paths those clients traced through life. Furniture was built-in, an extension of wall and floor. Colours were drawn from the surrounding environment: earth, tree, lake, sky. Materials were utilitarian: plywood, timber, stucco, Alsynite. And the shape of the interior dictated the appearance of the exterior, not the other way around. Ultimately, such eccentricities kept Schindler’s houses from ever really looking like houses at all. They were—are—mysterious vessels rising from the slopes of Silver Lake and Los Feliz and Studio City, forecasting a ‘life of the future’ that only Schindler seemed to grasp.

The architect was as stubborn and idiosyncratic as his architecture.

The architect was as stubborn and idiosyncratic as his architecture. Every morning Schindler put on a heavy white silk middy of his own design, with a low V-neck and a high, soft collar. He tried to seduce nearly all his female clients, married or single, and often succeeded. He served as his own general contractor, in part to cut costs for the artists, intellectuals, communists, and bohemians who tended to hire him, and in part so he could continue to sharpen his designs on-site. He was known to construct new chairs from leftover plywood in the garages of unfinished houses; later, once the owners had settled in, he would return to make small repairs himself, like a handyman.

Most of all Schindler refused to be fashionable. ‘I am not a stylist, not a functionalist, nor any other sloganist’, he once wrote, contrasting his work with the ‘rational mechanization’ of trendy International Style design, with its right angles, corner windows, and less-is-more functionalism. ‘The question of whether a house is really a house is more important to me, than the fact that it is made of steel, glass, putty or hot air’. The eastern establishment responded in kind, excluding Schindler from the Museum of Modern Art's seminal 1932 show in favour of his more doctrinaire rival Richard Neutra, a fellow Viennese and former friend who quickly became California’s most famous modernist. Schindler, meanwhile, slipped into obscurity—a footnote in his own time.

It was in 1935, at the start of this slow fade, that Ralph G Walker and his wife, Ola Fern, found their architect. They had seen another Schindler, the Oliver House of 1933, and heard its designer lecture at City College. Ola was an aesthete, a student of theatre and poetry and Japanese flower arranging; she thought a Schindler house would suit her. Together, Schindler and the Walkers selected a steep lot above the Silver Lake reservoir. The dramatic view resembled a postcard from Lombardy: the terracotta roofs below; the still, silent water reflecting hill and sky; the radiant San Gabriel Mountains.

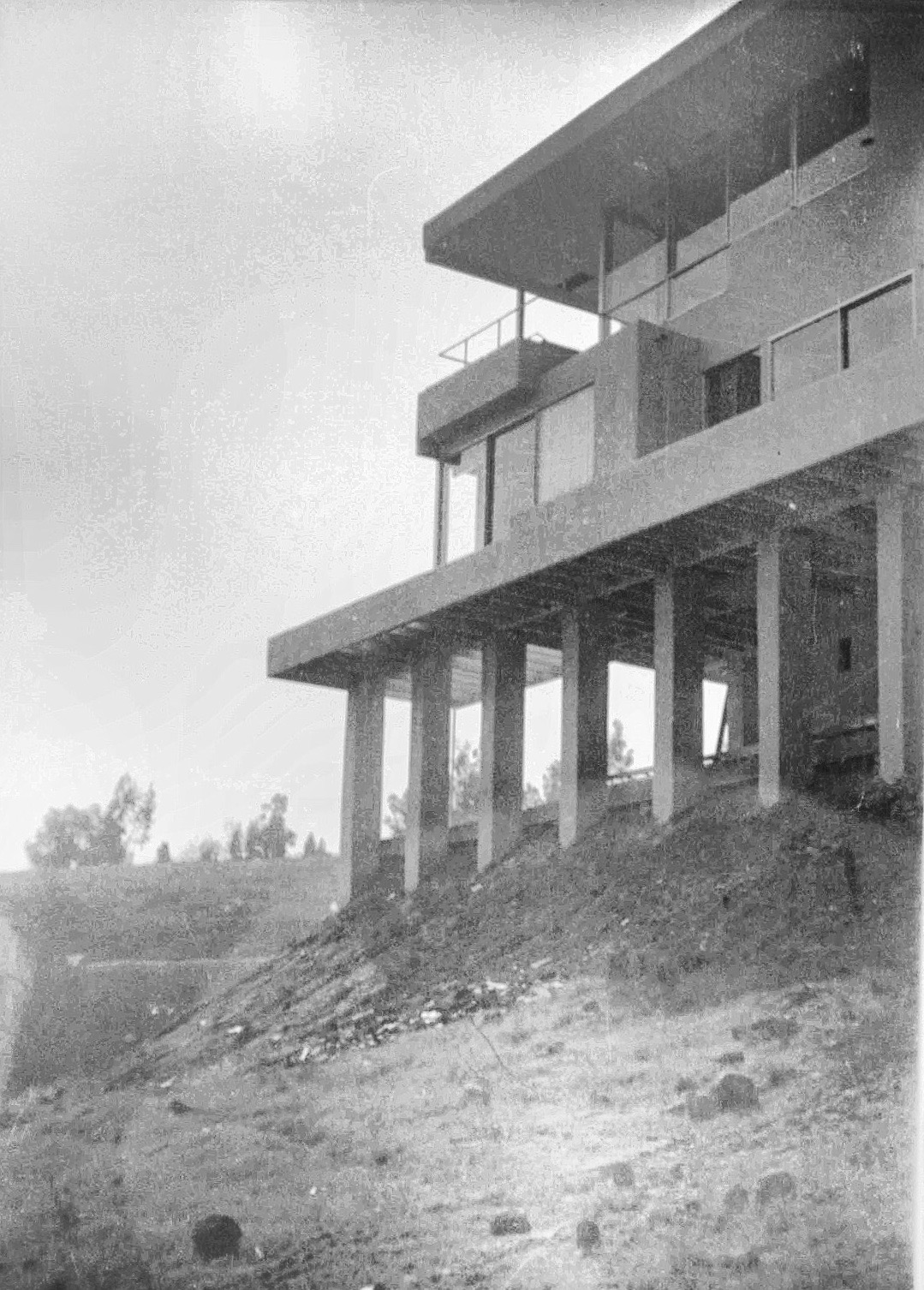

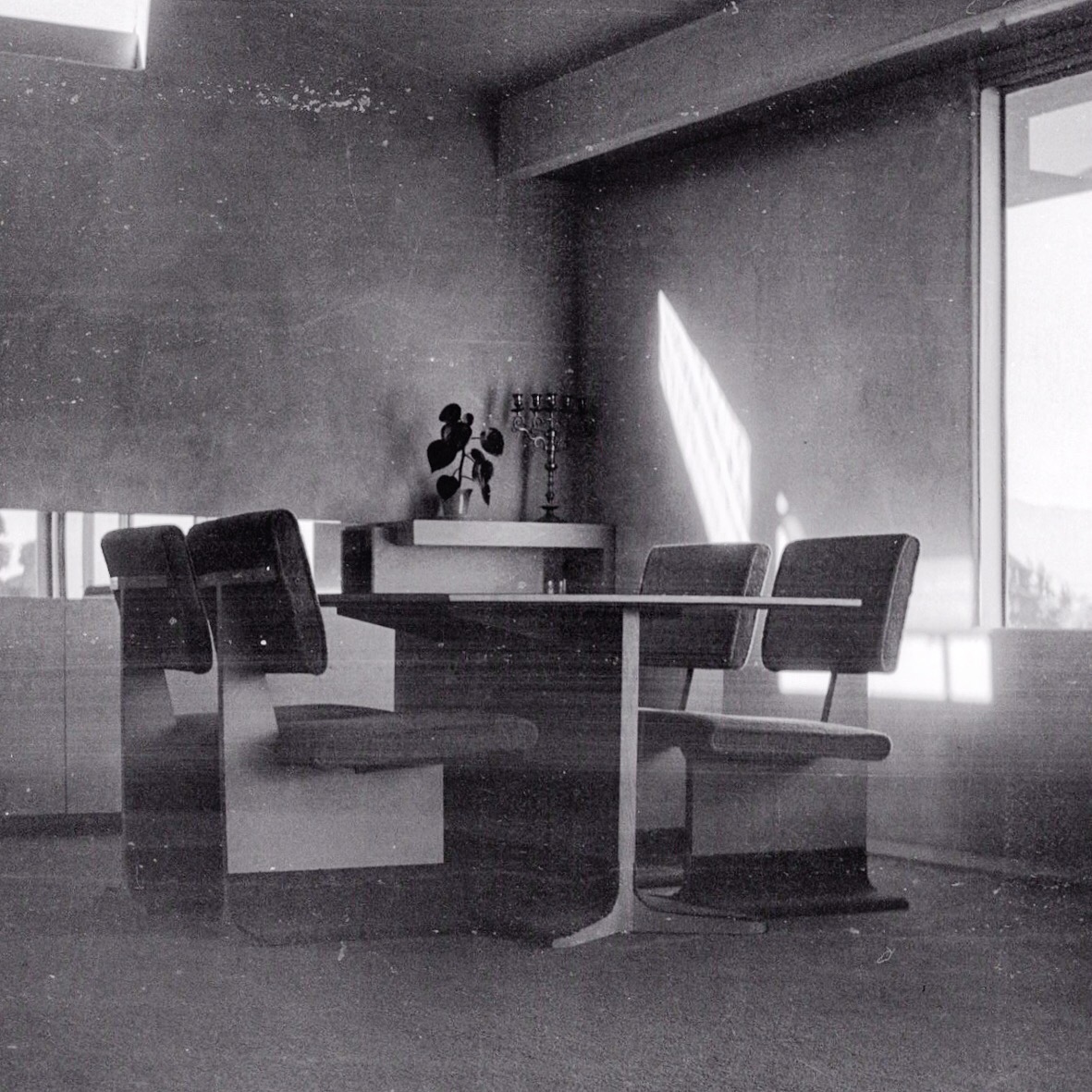

The following spring Schindler finished the Walker House. It was one of his most assured designs. A stark, linear street façade, and behind it, a collision of forms that splay, sprawl, and cascade down the slope. A ceiling pitched in several directions, with sunlight glowing through glass walls and clerestory windows on all four sides. Three balconies overlooking the lake. An ikebana room for Ola, tucked off the landing between the upper and lower floors. Walls of blue-green plaster fitted with cabinets, shelves, vanities, and desks of blondish Oregon pine. And beneath the bedrooms, eight tall pillars enclosing a shaded outdoor terrace.

Today, 80 years later, the Walker House is ours. I’m still making sense of how this happened. My own intensity certainly had something to do with it. When my wife and I first moved to Los Angeles in 2013, we were offered the opportunity to buy Schindler’s final residence. I had never heard of Schindler before. But the space changed me. I remember standing in the living room, absorbing its strange geometry, and realising, suddenly, that I was conversing across the decades with someone who had already anticipated the experience I was having. I was enveloped by his ideas: ideas about how I would see, how I would move, how I would live (if I were to live here). Schindler’s architecture was immersive in a way that most art wasn’t. I wanted to continue the conversation.

I bought every book on Schindler. I tracked down every magazine article. I even began to knock on doors. A startling number of Schindler owners invited me in and showed me around. It was a crash course in California modernism. I learned a lot.

I bought every book on Schindler. I tracked down every magazine article. I even began to knock on doors. A startling number of Schindler owners invited me in and showed me around. It was a crash course in California modernism. I learned a lot.

Then the deal collapsed.

In time we found another house. It wasn’t a Schindler—in fact, it was more International Style than anything else—but it was lovely. Our daughter was born two years later, after a long struggle to conceive. We thought we’d never leave.

Until we found out, shortly after her seven-month birthday, that we were having another kid.

It was in this state of shock that I started to fantasise about the Walker House—a proper three-bedroom, in our neighbourhood, in nearly original condition. A few weeks earlier, I had wheeled my sleeping daughter’s stroller up to the door. The owner was battling Alzheimer’s, but her middle-aged daughter had welcomed me into the living room and shared her email address. I decided to message her about our situation.

‘One of the consequences of this unexpected news’, I wrote, ‘is that we will have to move at some point in the future. My dream is to move into a Schindler: to fix what needs fixing, to preserve what doesn't, and to act as good stewards of great architecture so that future generations can enjoy it just as much as previous generations have’.

‘If you and your mother ever decide to sell the Walker House’, I added, ‘I hope you'll think of me’.

Two weeks passed without word. And then, finally, a short response. ‘We can't sell the house yet’, she wrote. ‘But I do plan to sell it later’.

I’d like to say I played it cool. I didn’t. Over the following year I emailed many, many times. At first the owner’s daughter said she might rent us the house. Then she said that she didn’t need tenants after all. Fearing a future bidding war, I asked if she would consider selling to us directly, off-market, when the time came. ‘Probably not’, she responded. ‘My brother is a realtor and he wants to get the highest possible price’. Even when she wrote after months of silence to tell me her mother had passed away and she would soon inherit the house, I wasn’t hopeful. ‘I still do not plan to sell the house immediately’, she said, ‘but probably will within the next couple of years’. Years. Our son was due in six weeks. I asked again about an off-market sale. No response. Then again, three months later, at the start of 2017. Nothing.

My obsessiveness had reached its limit. And that’s where luck came in.

One day last April, 15 months after my initial visit, I strolled past the Walker House again, this time with my napping son. The woman who had inherited the house was standing outside. ‘Oh, I meant to tell you’, she said. ‘I’m planning to put it on the market this spring’.

For the next 10 weeks, I rarely got a good night’s sleep. To buy, we needed to sell. Yet we didn’t want to end up homeless, so what we really needed was someone who would agree to pay top dollar for our current place—otherwise we could never afford the Walker House—while also agreeing to let us out of the contract if we didn’t get the Schindler. This was asking a lot. But somehow, after a few private showings, we found him: the most patient buyer in Los Angeles.

Then it was a question of competition. I’m a journalist. My wife writes for children’s television. In a swathe of the city where houses, particularly architectural houses, tend to close above ask, the Walker House was set to list at a price that was already beyond our means. I had nightmares about some young comedian casually outbidding us.

At last the day came. June 19, 2017. We submitted our offer—list price—and waited.

We heard back the next day. Ours was the only offer they had received.

I’ve woken up in the Walker House every morning for months now, and I still can’t understand why no one fought us for it. Yes, the bathrooms are small. Yes, the kitchen is challenging. But then there’s the sliding front door that seems as if it were salvaged from some ancient Japanese ryokan. The banded screen of plywood and glass that shields the living area, for privacy, while neatly framing a panorama of lake and landscape beyond it. The weave of cabinets wrapping every corner, with crannies for every imaginable object. The built-in, head-to-toe twin beds in my daughter’s room, with long ledges for books and plenty of space to curl up and read. The near silence at midday, punctuated only by the chirping of birds and the rustling of leaves in the wind.

Photo courtesy of the Architecture and Design Collection at the University of California, Santa Barbara

I could go on. But Schindler was right: you really can’t reproduce his work on paper. The cumulative effect of each of these details—each of these moments—is what the architect called ‘charm’. In an unpublished essay written while he was designing the Walker House, Schindler argued that ‘most American building influenced by the new European trends stops at the point where it has made the modern house merely more structural or functional than the conventional building’.

‘This is wrong’, he continued. ‘The design should go farther. The house, like any personality, finds fulfilment not in efficiency or strict style but in charm’—a feeling that also ‘fits the personality of the user of the building’.

The house, like any personality, finds fulfilment not in efficiency or strict style but in charm

Charm is a telling word. It connotes the ineffable, the magical, and above all, the communal. It can only exist in the relationship between two things—in the space between charmer and charmed. I won’t say the Walker House was ‘meant to be’ our home. But when I consider why I wanted it so badly—why it was, and is, my dream house—I keep returning to this idea of communion.

The daily dialogue I carry on with Schindler is one thing; it’s fascinating to inhabit his ideas about design. But ultimately it’s too late in life for me. The die has been cast. I’m thinking instead about my kids. What will it be like for them to grow up in this monument to one artist’s audacity, vision, resolve, and passion—his refusal to compromise, to settle, to conform? This is the space in which my son and daughter will learn how to live. I hope the choices that Schindler made in shaping it can shape them as well, and teach them how, in some small way, to live as he did. That, I suppose, is the dream.