In Palm Desert, Stayner Architects restore a modernist house to its former splendour

Interview by Jack Byron

Photography by Tim Hirschmann

One of the most pioneering and innovative architects operating in the 'tabula rasa' haven of Southern California was the modernist Walter S. White – a prolific inventor who pioneered new construction systems in his desert residences.

The Wave House, located in Palm Desert, is one of his most flamboyant and well known houses - renowned for its distinctive wave profile roof. Built in 1955 for artist and 'local lothario' Miles C. Bates the house, dilapidated by years of neglect and careless additions, it was recently meticulously restored to splendour by Stayner Architects.

We sat down with Christian Stayner to discuss the process of restoring the iconic house and Stayner Architects' holistic approach to architectural practice.

You bought the dilapidated Wave House at auction during Modernism Week 2018: how did you realize it was a significant piece of architecture that deserved to be saved?

On some level, from architectural training, you're able to dissect a building in its existing condition and it was obvious what had been added and altered. Early on we made use of the architecture archive at UC Santa Barbara: we went from walking the property and being able to visually pick it apart to actually knowing what was happening and being able to construct in our head as it was originally designed.

Luckily a lot of stuff had been added and very little had actually been removed from the building. We dove directly into the architect's original drawings from foundations to construction details which were definitely helpful.

Archival Photo: Kitchen

Archival Photo: Living Area

How did you decide which elements to restore and which to replace with contemporary materials or techniques?

The sort of relationship that our work has with history is in some ways opposite to how most people think about Los Angeles architecture. The generations before Gehry and Morphosis, even mid-century modernism, was very much about starting from scratch in Los Angeles. A tabula rasa where you made your mark and after 20 years it was demolished and replaced with something else that was largely agnostic to what came before.

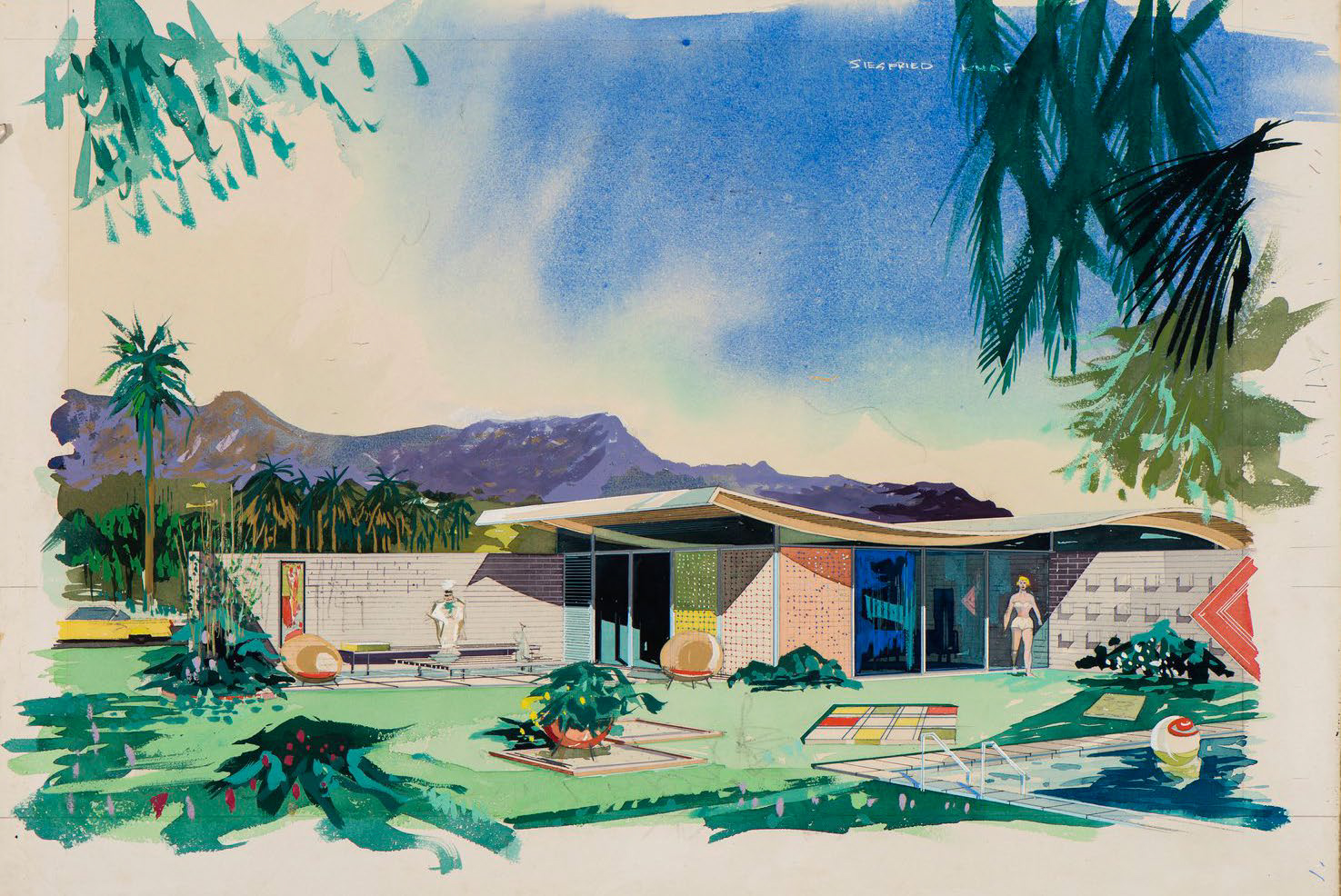

Archival Pre-Construction Rendering, South-West Corner

Date: Approx. 1954-1955

In terms of the Wave House, we felt that preservation can be a form of dogmatism. Rather than approaching it as restoring everything to 1955 standards versus modernizing and putting our mark on the house, our approach was to understand what the original architect's intent was. In many cases that intent had failed and I think that were he still alive, he would probably acknowledge that there were certain failures.

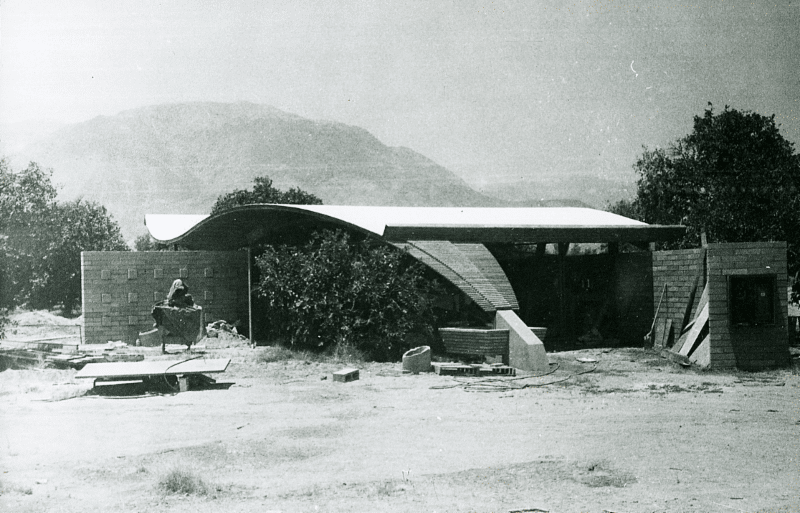

Archival Image of Construction, South-East Corner

Date: Approx. 1954-1955

Wherever possible we tried to realize the intent that White was trying to realize. For example: mechanical systems, there were some groundbreaking ideas. I don't think anyone else back then was doing geothermal underground distribution of HVAC. It sort of worked, but if he was using equipment 60 years more advanced, it would have worked much better. A lot of the things that we added into the building were an attempt to resolve some of the issues that he had not been able to resolve for lack of budget or lack of technology. In other cases we decided that wasn’t required, we didn't want it to turn into a stage set, which we'd seen at a couple of the modernist houses in that area.

We felt that it was important to reflect the full history that the house had from when it was constructed all the way through to the current period. And so there are very subtle things that we did, like all the new interventions that we made are in stainless steel. They're very clear as to what's sort of been added or when it's not original. For instance, there was a ceramic sink that we decided rather than replacing it with a similar vintage ceramic sink or porcelain sink that we'd replace it with stainless steel in order to show that change.

You furnished the house with your own pieces, tell us little about that process?

I have a furniture hoarding tendency which was made all the worse by living in the Midwest for a number of years where there’s amazing furniture production. Some of the objects are family items: magazines that were my grandfather’s, that have his address stamp still on them, stuff that was collected by my grandmother and my parents.

We also had a connection with Sam Reich, the grandson of Tibor Reich, a Hungarian-British textile designer best-known from the late '40s through the late '60s. Sam’s re-issuing some of his grandfather's designs and he was really generous and provided us with textiles for the house.

we felt that preservation can be a form of dogmatism...our approach was to understand what the original architect's intent was

You plan to build other structures there and open a small hotel, can you give us a preview of what that will be like?

It’s sort of a micro-microhood: we’re building two additional dwelling units and they'll be rented out as a very small boutique hotel with a pool. We’ve got planning approval for the project and now we're looking at construction.

I think one of the really interesting things that hasn't been reported about the Wave House is that Walter White patented a technique of timber construction 60 or 70 years ago for the roof that was a forerunner of CLT (Cross Laminated Timber) construction that’s been used in Scandinavia for the last 20, 30 years. We're looking at taking some of the original ideas that White had and trying to push them forward.

So while the form and all the aesthetics of it are not going to be a replica of the original house, we very much see this as like picking up some of the elements that he was working on and continuing that conversation. We've intentionally chosen very simple roof forms in order that the original roof maintains its flamboyance.

It's about wanting to have an engagement with those conditions that set up how you make architecture.

We're sitting here in a restaurant that you not only designed but also own and operate. That's unusual, you have a very holistic approach to the practice of architecture

Our practice is more or less split between projects that we develop, in many cases construct and increasingly try to hold and operate, and then our more conventional client commissions in the domain of educational or public benefit clients. They’re not necessarily nonprofits, but there is some sense of engagement with the cultural landscape.

We spend a lot of effort trying to understand what the limitations are on a project. Financial, programmatic, operational, legal in terms of planning and zoning and those considerations that are often a preset for the architects coming into a project or that the architect doesn't necessarily engage with. We’re more of an adviser and partner with a lot of our clients; we like doing work that has some sort of long-time benefit, not just quick financial return.

It's about wanting to have an engagement with those conditions that set up how you make architecture. And I think in that way, Walter White was a really interesting analog to our own practice. He was actually very much engaged in a lot of the construction and to a lesser extent the development of the work.

That's where we've landed in terms of how we're trying to structure a practice that is not 100% introverted and making work only for itself. We've been intentionally careful to avoid formal signatures to our work. I think that we've developed a sort of sensibility or attitude that is consistent across the work that we do. What role does the architect play or can the architect play and how do you feed back those restrictions or limitations into making form and space?